By Josh Wirtanen

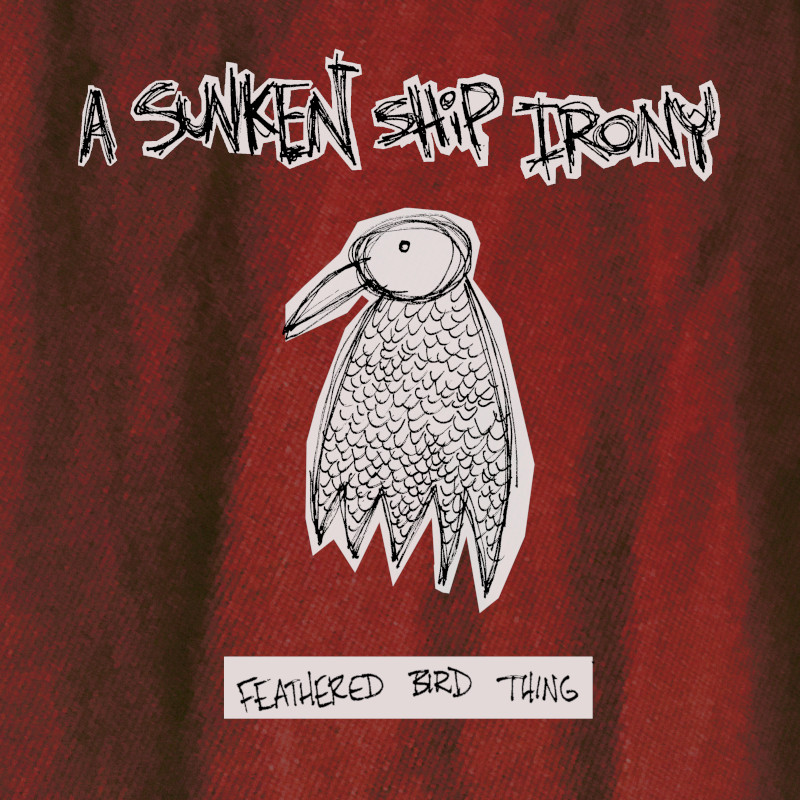

In August of 2022, A Sunken Ship Irony put out an EP called Feathered Bird Thing. This EP’s cover art features a rough drawing of a critter that resembles a bird. Is that just a random sketch, or is there a deeper meaning to it?

Well, the answer is both, actually.

The image originated in my head late one night when I couldn’t sleep. It just appeared to me out of nowhere, but once it showed up in my imagination, I couldn’t shake it. I fell asleep after a while, but when I woke up in the morning, the image was still there, along with the words “feathered bird thing.”

So I did the only thing I could think of, and I grabbed a pen and drew it, then captioned it “FEATHERED BIRD THING.” At that moment, I realized I had just come up with our next album cover.

If the story ended there, one could call this a mystery solved. The “feathered bird thing” is just a random and spontaneous artistic flash that happened during an episode of insomnia. But there’s actually way more to it.

I should warn you, this is where things start getting really dark.

Toward the end of 2021, I was diagnosed with kidney cancer. Kidney cancer is one of the “gentler” forms of cancer, and it has a 95% survival rate when caught early. But any cancer is still cancer, and there was a 5% chance this thing was going to kill me — a chance that would continue to grow if I let this thing fester. So the nephrologist decided to cut it out of me — he scheduled a partial nephrectomy, which is what it’s called when part of a kidney is removed (and also the title of the closing track on Feathered Bird Thing). The surgery would happen in mid-December of 2021.

It was supposed to be a simple surgery. If all goes well, the nurses told me, they’d give me some painkillers and send me on my way. I might be home that same night.

But all did not go well. I don’t know specifically what caused it, but there was some sort of complication where my kidney wouldn’t stop bleeding. My hemoglobin levels got so low that I was a hair away from having to get an emergency blood transfusion. But just before that happened, my levels miraculously stabilized.

I didn’t get to go home that night. In fact, I ended up spending four days in the hospital. Before the fourth day, I couldn’t even get out of bed — with or without assistance. On the morning of the fourth day, I was finally allowed to eat solid food again, so I asked for an omelet. And maybe this is just because I was tired of living off weak chicken broth and even weaker coffee, but I thoroughly enjoyed that hospital-cafeteria omelet. Swiss cheese and mushrooms. Delicious.

While I was eating my breakfast, a nurse came in and told me I could go home. That seemed kind of weird to me, because I didn’t feel like I was in any condition to take care of myself. But if the medical professionals said it was time to go home, I wasn’t going to argue. I got a ride to the pharmacy to pick up my prescribed painkillers and then back to my apartment.

However, the blood loss left me severely anemic. In fact, I’ve since told multiple nurses what my hemoglobin levels were when they released me from the hospital, and their first reaction is always the same: They tell me there’s no way that’s possibly true. Then they look at my medical records and confirm that I am indeed telling the truth; I was basically at Death’s door when I left the hospital.

My first day home was mostly spent sleeping, but the following day, I was feeling extremely weird and I couldn’t move. I called the hospital and was told to come back in immediately. I believe I spent something like 14 hours in the emergency room that day. That might have been the worst day of my entire life.

I didn’t have a chance to eat anything before getting rushed off to the E.R., and I hadn’t even had any coffee yet. On top of that, I was coming down off Ativan, which I had been taking intravenously for the entire time I was in the hospital. For some reason, they wouldn’t let me eat or drink anything in the E.R., even though my hemoglobin levels were dangerously low.

So there I sat, severely anemic and dehydrated, not allowed to eat or drink, coming down off benzos and caffeine at the same time, and in severe pain without being offered any painkillers. I did finally make it back to my apartment, but that night was a hellish nightmare of fever dreams, hallucinations, and headaches that felt like being smacked with a hammer. My side ached intensely. The room spun around me. I would have thrown up if there’d been anything in my stomach.

But that was the worst of it. Once I got to the other side of that experience and my withdrawal symptoms began to subside, I was finally on the long road to recovery. The nephrologist told me it would be a good six weeks or so before I felt anywhere close to normal, and his estimation was not wrong. I basically spent those six weeks sleeping and playing Minecraft. I barely even got off the couch before the end of January, 2022.

Things were going fairly well for a while, but in April or May, I was starting to feel weird again. The pain in my kidney was getting worse and worse, and eventually I got to a point where I could barely even stand up on my own again. I ended up back in the E.R. a couple more times, but no one seemed to know what was going on with me.

Something about that experience completely broke my brain, leaving me in a chronic state of existential horror.

There are a couple different analogies I’ve come up with for what was going on in my head during this period. Here’s the main comparison I make: Several years ago, a transformer exploded right outside my bedroom window. It woke me up from a dead sleep at like 4 a.m. with this awful science-fiction sound and a blindingly bright flash of light. My muddled, half-asleep brain convinced me that a nuke had dropped. This was the end.

The panic I felt in that moment was extreme and primal. I was confronted with the end of my existence, and my body reacted by triggering every physiological panic response at once. That panic quickly subsided, but it did feel like I’d stood on the brink of oblivion and had briefly looked into the abyss. This is what it feels like to die; this is what an organism experiences the moment before their consciousness is snuffed out.

After having the recovery rug pulled out from under me in the spring of 2022, I basically reverted back to a similar state of severe existential panic. But this time it didn’t stop; it just became a persistent part of my emotional tapestry. I told some friends that I felt like a squirrel that was running from a forest fire, or a dog that has severe social anxiety who’s been brought to a party and just sits under a chair shaking uncontrollably. I experienced other emotions in that period, but only on top of, next to, or inside of the panic that engulfed me.

So I felt a sense of comradery with panicked critters that realize they’re about to die. Psychologically, there was very little difference between myself and an ant under the thumb of a cruel child.

And that’s why the image of that feathered bird thing stuck with me. I could relate to its plight in a very real and personal way. There was a feathered bird thing inside me that had a human hand gripped tightly around its throat; it was a dying creature whose automatic survival instinct has been triggered but is failing.

The feathered bird thing, then, represents the animalistic terror that immediately precedes the ending. The hand tightens; the flame of consciousness goes dark. There’s a moment before that happens, a moment where every survival mechanism kicks in and malfunctions at once — the denouement of being. And then comes oblivion.

To complete the image for the album cover, I set the feathered bird thing against a backdrop of a red curtain — yes, the final curtain.

When you stand at the precipice of death, it’s difficult to look away. This experience has given me a new perspective on life and death, an admittedly bleak one.

If Feathered Bird Thing feels like it’s completely obsessed with death, it’s because it absolutely is. In “Decompose,” I talk about how “We decompose. We all get old. We all will die.” In “Summer Nights,” I reiterate this sentiment with the line, “We all are gonna die someday alone.” And in the closing track, “Partial Nephrectomy,” I walk listeners through the experience I described in this essay, but through a series of tiny, seemingly disconnected details. In this context, you can see that I’m “counting every breath I take” because “The clock is counting slowly,” and when it stops, my flame burns out.

Since releasing Feathered Bird Thing, I’ve noticed that the critter on the cover has been affecting other people. I’ve been told the image feels “iconic,” that there’s something captivating about it. It’s simple and rough, but it starts to worm its way into people’s heads, the same way it wormed into mine. If you look closely, you can recognize oblivion in that bird thing’s beady eye. This is a critter that’s staring into the abyss while the abyss stares back. Once you recognize it, it becomes a part of you. There’s no escape. Every story has an ending. Everyone dies.